INTELBRIEF

October 27, 2022

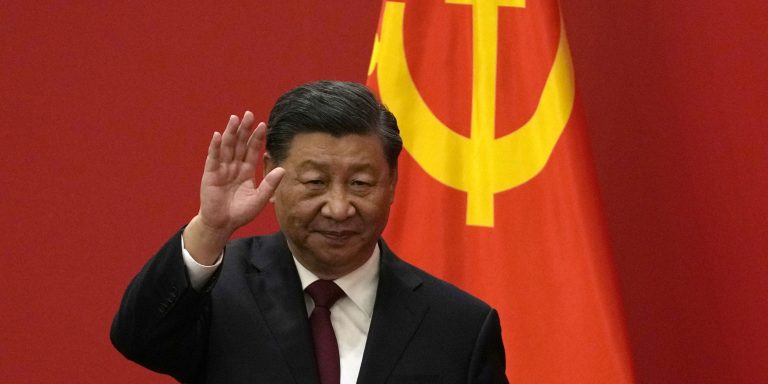

IntelBrief: The 20th Party Congress and the Continuation of China’s Increasingly Assertive Foreign Policy

Bottom Line Up Front

- During Xi’s decade-long rule, China’s foreign policy has become more assertive and aggressive, and the 20th Party Congress signaled a continuation of this trajectory.

- The Politburo Standing Committee is now completely made up of Xi loyalists, while those considered closer to former leader Hu Jintao have been ousted from the highest political body.

- Xi Jinping’s “yes-man” Politburo Standing Committee and the broader system of Chinese Communist Party rule have neither transparency nor accountability to voters.

- The 20th Party Congress signaled that the assertive foreign policy that has characterized Xi’s rule will remain in place and could even intensify, depending on geopolitical conditions and developments.

On October 22, the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) concluded. Chinese President Xi Jinping emerged from the week-long, twice-a-decade gathering as the People’s Republic of China’s leader for a third term with consolidated powers and a CCP top-tier leadership stacked with those most loyal to him. The Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), China’s most powerful decision-making body, was unveiled on the last day of the Party Congress and illustrated Xi’s centralization of power. All the other six PSC members are Xi proteges and staunch loyalists determined to support his grip on power. During Xi’s decade-long rule, China’s foreign policy has become more assertive and aggressive and the 20thParty Congress signaled a continuation of this trajectory.

The PSC is now completely made up of Xi loyalists, while those considered closer to former leader Hu Jintao have been ousted from the highest political body. Newcomer Cai Qi, current Beijing Party Chief, worked with Xi in Zhejiang and Fujian provinces for two decades and is considered a Xi loyalist. Wang Huning, a member of the PSC since 2017, is considered the ideological brain behind Xi’s rule. The former Shanghai Party Chief, Li Qiang, was promoted to the PSC, being selected as the number two on the committee, and is the most likely candidate for China’s next premier—showcasing that loyalty to Xi is more important than sustainable policy and experience. Li lacks the experience of having served as a Vice Premier, and after the disastrous two-month COVID-19 lockdown in Shanghai earlier this year, there was speculation amongst China watchers that he may have ruined his chances of receiving a promotion during the 20th Party Congress. Instead, Xi has elevated his former chief of staff from 2007 to the second-highest ranking official in the CCP.

Those not considered Xi loyalists were ousted from the PSC. Despite not having hit the widely accepted “seven up, eight down” retirement rule of the PSC (if a member is 68 or older at the time of a party congress, they will retire, but if they are 67 or younger, they may enter or remain on the committee) both the current premier, Li Keqiang, and Wang Yang did not remain on the committee. Both Li and Wang came up in the CCP through the Communist Youth League, which was previously considered an informal, yet powerful political faction that included China’s former leader Hu Jintao. Li and Wang likely did not meet the loyalist threshold for Xi. It’s important to note that appointing political loyalists to decision-making power positions is not a unique feature to China and happens in Western governing structures as well; however, the key distinction lies in the different systems of governance, where liberal democracies embody more transparency of policymaking and the threat of being voted out of office enshrines accountability to the voter. Xi’s “yes-man” PSC and the broader system of CCP rule have neither transparency nor accountability to voters.

During Xi’s decade-long rule, China’s foreign policy has become less constrained—departing from the Deng Xiaoping philosophy of “keep a low profile and bide your time.” Increasing militarization and patrolling of the East and South China Seas, the 2020-2021 Sino-India border skirmishes, and intensified military drills in the Taiwan Strait are but a few examples. Diplomatically, Xi’s rule has been characterized by confrontational diplomatic exchanges—dubbed “wolf warrior diplomacy”—and a rapprochement between Russia and China, with Xi and Putin announcing a “no limits” partnership between Beijing and Moscow just weeks before Russia launched its illegal further invasion of Ukraine on February 24. The 20th Party Congress signaled no change; instead, it is more probable that the assertive foreign policy that has characterized Xi’s rule will remain in place and could even intensify, depending on geopolitical conditions. When presenting the work report at the beginning of the Congress, Xi overwhelmingly focused on “security” of all forms as a principal priority. Xi stressed the need to protecting China’s interest abroad, highlighting “foreign interference” in Taiwan issues and an increasingly dangerous external security environment. He pushed on the need to maintain a “fighting spirit.” In addition, Foreign Minister Wang Yi, under whom “wolf warrior” diplomats have been cultivated, was promoted to the Politburo—the second-highest level of power in the CCP. Wang, who was expected to retire this year for being over the age of 68, is now likely to take on the position as director of the general office of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission. Xi’s ideological confidant, Wang Huning of the PSC, also contributed to the rise of “wolf warriors” in China’s foreign policy.

The likely continuation of assertive Chinese foreign policy comes at a time of increasing strategic competition between China and the United States. In the Biden administration’s National Security Strategy, released on October 12, China is portrayed as “the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to advance that objective.” As China doubles-down on a more assertive foreign policy, it is important that the United States heed the idea put forth in the Biden administration’s NSS, namely: “Our strategy [towards China] will require us to partner with, support, and meet the economic and development needs of partner countries, not for the sake of competition, but for their own sake.” The United States can achieve this by devoting more resources to diplomacy, providing sustainable investment to partner countries, acting as a reliable security partner, and not framing these actions as simply a means to an end to compete with China.