INTELBRIEF

February 1, 2018

TSC IntelBrief: The Continuing Stain of GTMO

- On January 30, President Trump signed an executive order rescinding President Obama’s directive to close the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay (GTMO).

- The order is more symbolic than practical, as Congress has long blocked transfers of those held at GTMO into U.S. prisons, but the symbolism is important.

- It costs over $10 million dollars annually to house one detainee at GTMO, compared with approximately $78,000 to house a legally-convicted prisoner in a maximum security federal prison in the U.S.

- The GTMO detention facility is still holding pre-trial hearings for the 9/11 conspirators, more than 16 years after the attacks.

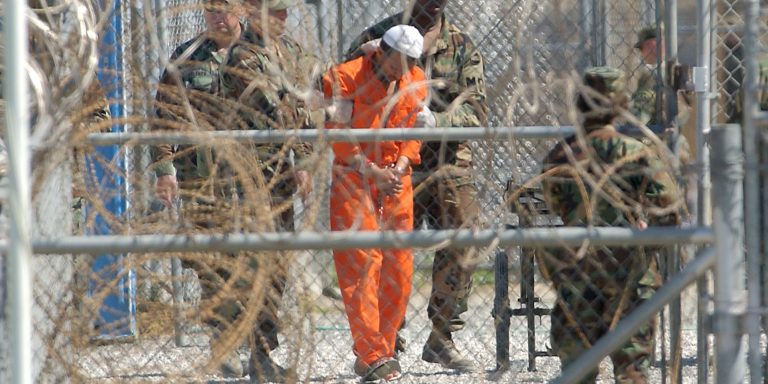

By every measure, the Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp (GTMO) is a remarkable failure. Opening it was a breakdown in moral leadership after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. That it has been kept open has come at great cost to the reputation and standing of the United States. It has not succeeded in its mission to bring justice to those accused of the worst mass murder in U.S. history. U.S. civilian courts, however, have successfully prosecuted hundreds of terrorist suspects in a transparent manner, and at far less financial and moral cost to the country.

On January 30, before his first State of the Union address, the White House released an executive order (EO) signed by President Trump that rescinded President Obama’s order calling for GTMO’s closure. The EO was not specifically mentioned in the speech, but the president did ask of Congress that ‘we continue to have all necessary power to detain terrorists, wherever we chase them down, wherever we find them. And in many cases, for them, it will now be Guantanamo Bay.’ There have been no transfers into GTMO since 2008, and there have been no transfers out of GTMO since President Trump took office.

In a failure of trust in the U.S. justice system—and a failure to stop using fear as a political and fundraising tool—Congress blocked the closure of GTMO by passing a law prohibiting the transfer of GTMO detainees into the U.S. The argument was that GTMO detainees were so dangerous, it would jeopardize national security if they were held in U.S. prisons. Because of the law prohibiting the transfer of detainees into the U.S., in practical terms, President Trump’s EO has a limited effect: GTMO wasn’t being closed in the foreseeable future. Further, it is unclear if new suspects will be brought to GTMO. But the symbolism of the order is significant, as it reaffirms that at the highest level of government, the indefinite detention of people suspected of terrorism is consistent with U.S. notions of justice.

780 people have been detained at GTMO since 2001; currently, there are 41. It costs over $10 million dollars annually to house one detainee at GTMO, compared with approximately $78,000 to house a legally-convicted prisoner in a maximum security federal prison in the U.S. Among the 41 are five men accused of direct involvement in the 9/11 attacks: Khalid Sheik Mohammed, Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin al Shibh, Ammar al Baluchi, and Mustafa Ahmad al Hawsawi. The case against these men is still in the pre-trial phase, with a tentative trial date set for 2019, 18 years after the attacks. The death penalty trial for Abd al Rahim al Nashiri, accused of planning the October 2000 attack on the U.S.S. Cole, is no closer to resolution.

Keeping GTMO open sends the erroneous message that the U.S. justice system cannot handle terrorism cases. That position denies reality and history. There is simply no financial, legal, or ethical argument that justifies the decision to keep GTMO open. It is a failure of both domestic and foreign policy.

For tailored research and analysis, please contact: info@thesoufancenter.org