One Ambulance Crew on the Frontline of Turkey’s Fight Against COVID-19

December 17, 2020

“The last eight months [of this pandemic] has been tough for us. There is more psychological fatigue than physical fatigue,” said Metin Eskisoy, a 23-year-old Emergency Medical Technician working in Istanbul with 112, Turkey’s health emergency hotline. With his two other colleagues, paramedic Dilek Çattikas, 27, and ambulance driver Yakup Erk, 38, they have been working 24-hour shifts every other day since the start of the pandemic in Turkey in March.

Worldwide, at least 7,000 healthcare workers have died from COVID-19 according to an analysis by Amnesty International in September. Beyond the physical toll taken on by frontline health workers is the mental stress and exhaustion that has set in after nearly a year since the pandemic began.

“In the early days of the pandemic, I thought we shared the same risk as our colleagues in the hospitals,” said Eskisoy. “But I’ve realized that we are often at a much higher risk of contracting COVID-19,” he continued, citing the unpredictable nature of the environment in which they work, Istanbul. As in many other places, ambulance crews responding to emergencies will often not know if the people they are treating are infected with coronavirus, raising the hazards of carrying out their work.

The Turkish government has come under increasing criticism for obscuring the true toll of COVID-19, making the scale of the crisis hard to grasp even as new cases continue to rise steadily. Such underrepresentation of the severity has the potential to minimize the scale of the threat for civilians, who may decide to flout recommended guidelines issued to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus.

“When I see people who seem as though they don’t care about this pandemic, like going outside without masks even though we know of ways to reduce infections, it lowers our motivation and enthusiasm to work,” said Eskisoy, speaking of the added burden to the fatigue healthcare workers face.

While frontline workers in Turkey are now better supported since the start of pandemic, they hadn’t often seen the pervasive reality of the disease reflected in official government statistics, which counted only symptomatic cases in its daily tallies until November 25. Deaths from the coronavirus are not always counted as such.

In Istanbul, Turkey’s largest metropolitan city with a population of approximately 16 million people, the 112 health emergency hotline serves as the lifeline for residents who are positive with coronavirus, or displaying symptoms.

All emergency calls go through the Provincial Ambulance Service European Command and Control Center – essentially the nerve center for ambulance operations on the European side of Istanbul – where dozens of staff and medical professionals, stationed in front of computers with maps of the city, answer the phones around the clock.

Activity buzzes – at least 40,000 calls come through the call center per day since the start of the pandemic. In an enormous room, each of the 309 full-time ambulances are dispatched and tracked along their routes. Almost all calls are now coronavirus-related.

For Eskisoy’s team, working in the densely populated Bahçelievler neighborhood on the south side of European Istanbul, their day begins promptly at 8am. The three-person team arrives at the base on a quiet street, their ambulance parked outside, ready to go for the day. The first calls start coming in almost immediately, often cutting breakfast short, and continue, usually without a break, for a full 24 hours until their shift ends.

According to Eskisoy and Çattikas, the team handles around 23 cases per day, retrieving residents to be transported to the hospitals. Some are confirmed to have COVID-19 and need to be hospitalized, while others display symptoms but are believed to be COVID-positive.

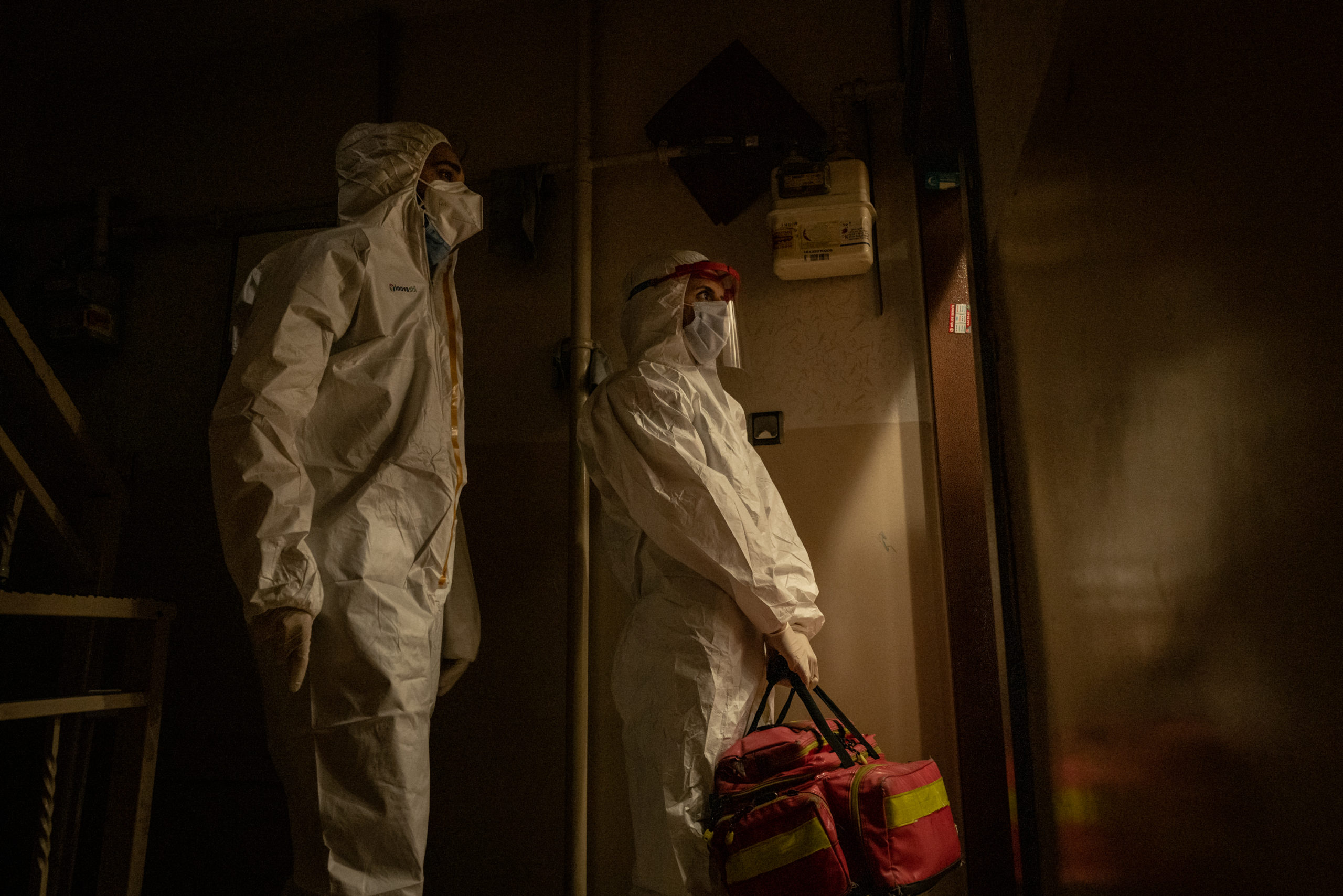

All the same, the crew responds to each call in a routine they have practiced so regularly it has become automatic. Çattikas writes down notes and details on a sheet attached to a clipboard while the ambulance driver, Erk, winds his way through the narrow streets. As the ambulance parks outside the building where they are to pick up the patient, personal protective equipment – including masks, face shields, gloves, and full body suits – are carefully adorned before they ring the doorbell.

After handling each case, the team disposes of their PPE and spends the next 15 minutes disinfecting the ambulance, ready to repeat the procedure again.

Despite the enormous psychological toll continually taken on the frontline workers, Metin says he is proud of being a part of the fight against COVID-19, but notes “we still cannot see the light in this darkness yet.”

Reporting from Turkey by Nicole Tung