INTELBRIEF

October 2, 2020

IntelBrief: The Security Challenges Presented by China’s ‘Health Silk Road’

Bottom Line Up Front

- China recently declared its intentions to deepen multilateral health cooperation with Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, China has revamped its ‘Health Silk Road’ as an instrument for Beijing to tout itself as a responsible global leader.

- China’s ‘Health Silk Road’ has seen the provision of bilateral medical aid and championing Beijing’s pandemic response in multilateral forums.

- The ‘Health Silk Road’ and China’s attempts at making multilateral inroads under the cover of the pandemic brings with it a host of security issues.

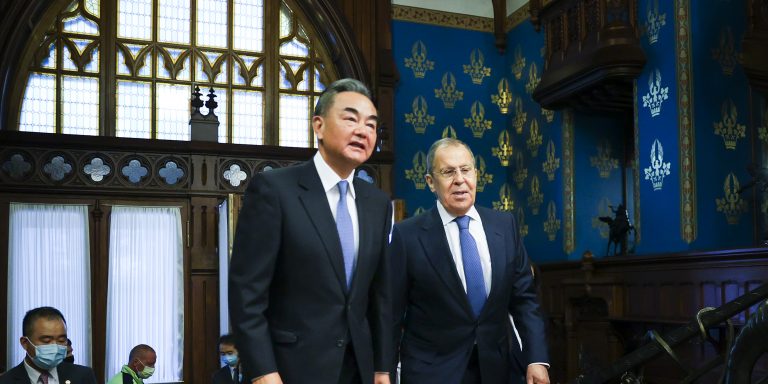

On September 17, official Chinese government media agency, Xinhua News, published an announcement by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi that China, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia had signed agreements to deepen multilateral health cooperation. This is but one example of Beijing’s efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic to revamp the concept of the ‘Health Silk Road’—a paronomasia on Xi’s signature foreign policy, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The concept was initiated in 2017 through a memorandum of understanding between China and the World Health Organization (WHO), which made ambitious, but vague pledges to build an international community of health cooperation. It has remained largely dormant, until the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the world, when Beijing has made use of the ‘Health Silk Road’ to boost its image on the world stage, as well as to protect and advance the economic and political interests of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

To advance its national interests, China has pursued several lines of effort under the banner of the ‘Health Silk Road’—providing bilateral medical aid, selling medical equipment, lending economic support, and championing Beijing’s pandemic response in multilateral forums, through diplomacy, and on social media. These actions serve to refashion China’s image on the world stage from being the arsonist of the pandemic to the firefighter—often highlighting European and U.S. butchered responses to control the virus and praising China’s successes. The ‘Health Silk Road’ also presents an economic opportunity for Beijing to reframe the BRI in the midst of the economic fallout from the global pandemic. The pandemic has highlighted vulnerabilities in labor and supply chains, as well as the economic unsustainability of Chinese loans. In a post-pandemic world, many BRI recipient countries may not perceive costly and ambitious infrastructure projects as attractive options. The ‘Health Silk Road,’ however, offers solutions that ensure Xi’s project will live on—even in an economically devastated world and in a time of a slower Chinese economic growth. Critically, the ‘Health Silk Road’ also offers an important narrative to China’s domestic audience—the CCP as a legitimate and responsible ruling party. Beijing seeks to juxtapose its response to COVID-19 to that of liberal democracies like European countries and the United States, which have suffered more from the pandemic.

There are several security issues and challenges accompanied by China’s ‘Health Silk Road.’ First, these ostensibly benevolent engagements have also been accompanied by more malicious actions, such as sophisticated disinformation campaigns, intimidation, ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomacy, and cyber-attacks. Such actions raise questions about China’s true intentions and geopolitical ambitions. For example, when aiding Italy at the onset of the pandemic, China also sought to amplify anti-EU sentiment in the country with the aim of sundering European unity and straining trans-Atlantic relations. Second, the prospect of China marrying the ‘Health Silk Road’ with the ‘Digital Silk Road’ threatens to further aid authoritarian leaders and stifle human rights in BRI countries, by exporting emerging technologies used for surveillanceunder the guise of increasing public health and security. Third, China’s actions have been met with criticism from local populations, while leaders turn a blind eye to avoid damaging important economic relations with Beijing. The same day that Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Mongolia, popular protests erupted in Ulaanbaatar criticizing the CCP’s restrictive ‘assimilation policies’ and violent crackdown targeting minorities, including ethnic Mongols, in China. Similarly, protestshave taken place in Kazakhstan over China’s oppression of ethnic Kazakhs, Uighurs, and other minorities in Xinjiang. Thus, while touted as an inclusive program, the ‘Health Silk Road,’ could serve to destabilize regions, solidify authoritarian tendencies, and further infringe upon the sovereignty and independence of a number of countries.

While the United States has recoiled from a leadership position in the midst of a global crisis, China is taking advantageof the vacuum to further its own interests and claim the position as a responsible world leader. Utilizing the ‘Health Silk Road’ to engage and deepen multilateral ties with Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) members signals that China is seeking to harness policies like the BRI, and forums, like the SCO, to further solidify its position on the world stage. In addition, Chinese leadership and diplomatic engagement with SCO countries also suggests that the organization now serves as a springboard for Beijing to forge consensus and cooperation with members outside of the traditional security issues it was originally created to address—something that could cause geopolitical ripple effects in the region and beyond.