INTELBRIEF

January 22, 2021

IntelBrief: A U.S. About-Face on Climate Change

Bottom Line Up Front

- On his first day in office, President Biden announced that the U.S. would rejoin the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

- The Trump administration’s 2017 announcement to leave the accord just took effect on November 4, 2020, but was still a symbolic blow to U.S. soft power.

- The last four years have witnessed U.S. political leadership repeatedly dismiss climate change, while seeking to move forward with increased coal production.

- Climate change and national security are inextricably linked; the nexus already impacts economies, as well as water, energy, and other critical resources.

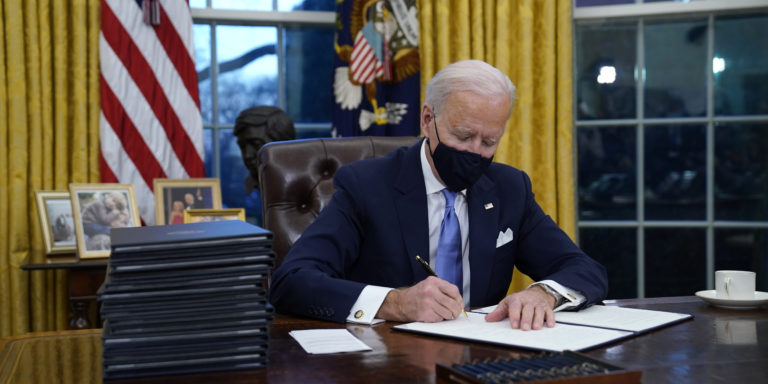

With the stroke of a new president’s pen, the United States of America rejoined the Paris climate agreement. Still, it will take much more than a change in administrations to regain a position of leadership on the issue of climate change and ‘climate security’ more broadly. U.S. government action and commitment to address climate change has, for decades, been mercurial at best. The previous administration politicized the issue to an extraordinary degree, even against the backdrop of uneven US engagement - including the 1998 refusal to join the Kyoto Protocol and high-level denigration by senior US leaders of the science underpinning climate change. During the course of the last four years, Washington has withdrawn entirely from consensus-based efforts to work multilaterally to tackle challenges like climate change. This trend accelerated even as Beijing began to assume a more active role in multilateral bodies, presenting an image of China as a country willing to work with international partners across a range of issues from development and public health to security. The Biden-Harris administration will be more aggressive in assuming a more traditional U.S. leadership role on global challenges while remaining cognizant of the importance of soft power, access, and influence.

Perhaps understandably, the rest of the world may struggle to have full confidence in American resolve, particularly when U.S. commitments can be done and undone by executive order. This uncertainty has risen in an unprecedented manner over the past four years. But as long as American politics remain dysfunctional, the executive order will be one of the few ways in which an American president can move toward concrete action. It will therefore be important to ensure that the actions to implement Executive Orders can be implemented and institutionalized. A more consistent and irreversible approach would be to establish a sustained campaign to better inform the U.S. electorate about the domestic cost and global impact of climate change. 2020 was the second-hottest year on record since data started being recorded. The ten hottest years on record have all been in the last 20 years and the trend is worsening.

A goal of the Paris accords is to keep the rise in global temperatures below 2.0 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit); each country is to set its own goals in reducing emissions of greenhouse gases that are a major driver of accelerating climate change. A purely transactional approach to international consensus-based agreements was evident in Washington’s relationships over the past four years with its key allies, including many in Europe, which did little to build effective responses to complex global challenges like accelerating climate change. In this instance in particular, combating disinformation is critical as widespread support for the conclusions drawn by scientists and experts is necessary to develop and implement sustainable changes.

Accelerating climate change is already a multidimensional challenge—national security, public health, and the economy cannot be viewed in isolation. For example, the evolution of transnational terrorism over the past two decades has highlighted the importance of local conflicts and grievances in driving regional and even international insecurity. Groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS leveraged frustrations, grievances and needs at local levels and linked them to global narratives and resources. Consequently, regional affiliates have been able to draw on preexisting conflicts and tensions to mobilize support. Water scarcity leading to food shortages will create new conflicts and worsen existing ones, as rainfall patterns change and periods of drought punctuated by devastating floods become the new normal. This, in turn, could lead to ‘climate refugees’ and drive chaotic patterns of irregular migration. Domestically, the rise in sea levels will impact the U.S. eastern and gulf coasts, threatening cities, naval bases, and natural habitats. Persistent worsening drought will continue to plague the western regions of the U.S, as it does in Europe and in Asia. Climate scientists are concerned that much of the coming change is already ‘baked in’ to the equation, meaning that action is needed immediately to avoid some of the most dire predictions. Already, the U.S. population is reeling from the socioeconomic impact of a pandemic, in addition to the grievances and frustrations that have been voiced by those willing to use violence against the government. With the U.S. now committed to a leadership role, and with the appointment of committed experts and policymakers, the Biden-Harris administration has taken the key step to begin to mitigate some of the worst-case scenarios. Climate envoy John Kerry will need to move quickly to work with international leaders and organizations to translate this into meaningful next steps, and allow key partners to consider international peace and security issues through a ‘climate security’ lens where relevant.